Trust in brands is illusory, just look at Facebook’s continued growth

Facebook repeatedly ranks low in consumer trust surveys, yet user growth continues, revealing the idea of trust in brands as anthropomorphic nonsense.

The young woman stiffened in her chair. She looked out at the half-dozen faces of the US Senate subcommittee and then returned to her prepared statement. “I’m here today because I believe Facebook’s products harm children, stoke division and weaken our democracy,” Frances Haugen explained. “The company’s leadership knows how to make Facebook and Instagram safer but won’t make the necessary changes.”

The young woman stiffened in her chair. She looked out at the half-dozen faces of the US Senate subcommittee and then returned to her prepared statement. “I’m here today because I believe Facebook’s products harm children, stoke division and weaken our democracy,” Frances Haugen explained. “The company’s leadership knows how to make Facebook and Instagram safer but won’t make the necessary changes.”

Haugen’s testimony made global headlines this week. Her accusations have been levelled at the social media giant many times before. But this time, coming as it did from someone who had worked so recently at such a senior level within Facebook, the charges appeared more pointed and damaging than before.

Haugen joined Facebook in 2019, working in a team dedicated to removing misinformation from the company’s social media platforms and bolstering its ‘civic integrity’. But the more she worked, the more disillusioned she became. When Facebook dissolved the civic integrity team last year, Haugen finally realised, “I don’t trust that they’re willing to actually invest what needs to be invested to keep Facebook from being dangerous.”

Facebook’s Horizon Workrooms sucks ass

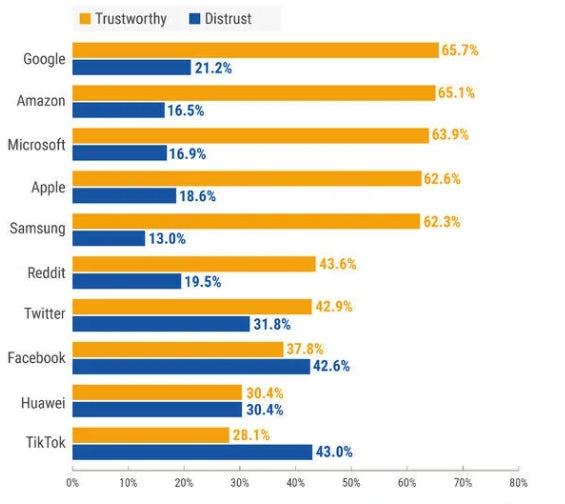

Facebook cannot be trusted: it’s a message that has been aimed at the company so many it has almost become expected. And it’s certainly a message that resonates with users. Look at any survey from any country over the past five years and, inevitably, at the bottom of the trust list, skulking down in the murky depths with Chinese brands TikTok and Huawei, is where we almost always find Facebook. People, many of its own users, simply don’t trust the company.

And, contrary to popular opinion, that is not simply a function of Facebook’s digital status. People can and do trust digital brands. In surveys of consumer trust, both Google and Amazon often appear not only higher than Facebook, but above almost all the other brands – digital or not – in the league tables. There is something about Facebook that engenders mistrust and disquiet.

These endemic levels of mistrust usually spark a second, all too common observation about Facebook: that the company is imminently fucked. The logic of the argument is as simple as it is prevalent. One of the most important building blocks of brand success is customer trust. Without trust brands are in trouble. Ergo, Facebook’s status as probably the world’s least trusted brand and its ongoing crises of truthfulness will lead to inevitable unpopularity among users. This will ultimately result in a downturn in usage and then to financial ruin.

Except none of that has happened. In fact, the opposite has occurred. Across the murky, smoke-filled decade that has surrounded Facebook, two clear facts emerge. First, that the company has low levels of public trust that have consistently declined in more recent years. Second, that same company has grown its commercial base on every possible level over the same period. Penetration is up, revenue is up, profit is up, share price is up.

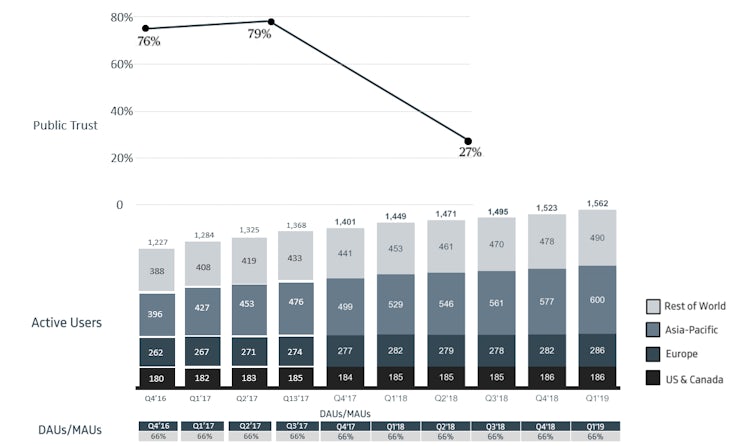

Gaze at the chart below with the appropriate level of wonder. Because whatever you think of the company, its marketing performance is wondrous. Wondrous because of the sheer size of its user base – almost 2 billion people. Wondrous because, with almost no exception, that user base continues to grow. And wondrous because, despite that enormous established user base and continual growth, it’s DAU (daily active user rate) remains consistently and addictively the same.

Over a decade of reporting, Facebook achieves an incredible double whammy of platform performance: its user base keeps increasing while its daily usage never declines. Today, like every other day, two thirds of 2 billion people will open up Facebook.

But what does that tell us about trust and its importance for brands? Almost every $10 presentation about branding bangs on about trust and its importance. And yet here is the least trusted brand on the planet posting perfect performance numbers in the face of one of the greatest deficits in trust ever recorded.

What do we make of the fact that during the period of Facebook’s greatest evaporation of trust – the heady days of 2018 – the platform resisted any loss in users or usage time. As you can see from the overlay of brand trust on top of quarterly growth in the chart above, Facebook grew its numbers during Q1 when the Cambridge Analytica scandal blew up, and in the following quarter when Zuckerberg delivered his infamously unconvincing explanation to Congress. And all the quarters since then.

If I had watched that stilted performance or believed the slew of column inches that followed it, about Facebook’s abject lack of trust and its imminent decline, I might have been convinced to sell my shares in the company. That would have been a massive error. In the intervening three years since Facebook “obliterated all trust in its platform” the company’s shares have doubled in value.

Trust is not fundamental to branding

As evidence-based marketers, we are faced with only two possible explanations for all of this. Either Facebook is cooking its numbers in an act of corporate malfeasance unprecedented in the history of public companies. Or, and this is the one I am betting on, trust is not quite as fundamental for brand success as the experts might have you believe. In fact, it might not even be a variable that matters one jot.

To even suggest trust is not a crucial building block for brand success is to push back against decades of established thinking. Since the mid 20th century, almost every explanation of brand equity has involved a significant section on the T word. Look in the index of any basic brand textbook and trust gets multiple reference pages.

Gary Vaynerchuk thinks you need to start by building a brand customers “know, like and trust”. Steve Jobs thought brand was “simply trust”. For Wally Olins, “creating and sustaining trust” was what branding was all about. The list is endless.

Comparing the original, human notion of trust with its corporate, branded equivalent makes it immediately questionable.

But go back a little further, and the idea that consumers need to trust brands would have been met with a quizzical 19th-century look. If you’d asked your great great uncle Robert whether he trusted his Woodbines, or your grandmother’s grandmother if she drank Boodles Gin partly because of the trust she had for the brand, both would have had thought you were suffering from an attack of the vapours.

And they’d be in the majority. For most of history, people saw a clear demarcation between humans and the products that they consumed. It was only in the 20th century, with the postmodern turn, that we began to anthropomorphise brands and the interactions we had with them.

Slowly, the concept of ‘loving’ a brand became accepted, popular and then enshrined in management thinking. We learned to build brand ‘relationships’ centred on making sure customers became ‘loyal’ to certain brands. And much of this was founded on that most humanistic of conditions – the idea of trust between consumer and brand.

But was this rush to anthromorphise everything actually a big old pile of bollocks? Most of these concepts that we held in such high regard in the late 20th century are now regarded by modern marketers as highly specious at best, and possibly complete nonsense.

The ideal of brand love died with the career of Kevin Roberts. We have spent a decade pouring a large bottle of cold, system-one water over the importance of brand relationships. And the cosy, lifelong marriage of brand loyalty has been replaced with the erratic, insecure excitement of ongoing polygamy. Never has Ehrenberg-Bass been racier.

But somehow trust survived this 21st-century cull. Mention customer loyalty or brand love and an army of ‘strategists’ will leap onto Twitter faster than you can say “survivorship bias”, to belittle both concepts. But brand trust survives unscathed and unobjected-to. After all, what could be more inarguable than trust being important to consumers and essential for brand success?

Brands aren’t people

And yet when you actually sit down and think about it. The whole concept seems eminently ridiculous. Comparing the original, human notion of trust with its corporate, branded equivalent makes it immediately questionable.

I trust my wife. Really, I do. I trust her with my children. With our finances. With the dogs. With the car – my god, the car! With my affections. My confidences. My everything.

When, hypothetically, her brother comes round with a big bag of weed and forces me to consume it with him, I trust her to come out in the middle of the night, explain to me that I am not “lost in a jungle far from home” but rather slumped face-first in the garden 3ft from the back door. And put me to bed. With a pat on the head and a bucket tenderly located right next to me. And I trust her not to bring this up the next day. Just to watch me limping into the kitchen the next day with a look that combines love, distaste and the security of knowing that there is nothing left to know.

I don’t expect any of that from brands. Sure, there are some base levels of reliability in there somewhere. But do they exist at a high enough level or across enough complex dimensions to qualify as trust as we think of it in human terms?

In Facebook’s case, do I need to trust the platform like a person? Do I even need to trust it to protect my data? Sure, if you ask me these two questions in a survey I might say they are important and agree that Facebook underperforms on both counts. But perhaps I expect none of this from the platform in my daily behaviour. Perhaps my patronage is predicated on much lower-level expectations: that when I click on the icon I immediately access my network and can see what is going on. The end.

This low level of expectation makes a lot more sense than the focus on higher-order trust. It also fits with the broader rejection of other anthropomorphic traits like loyalty and love being associated, all too easily, with brands. It might also explain why TikTok, another hugely untrusted brand, continues to grow at fercious rates of both penetration and usage. And this more mundane, basic concept of limited expectations would also explain why Facebook continues to triumph despite the abject absence of trust that most of its users and the population in general have for the brand.

I think consumers, as opposed to those who profess to be experts in studying them, know this. I think Mark Zuckerberg understands it too. He talks with studied, robotic focus about the need for trust while – I bet – being the giver of zero point zero fucks about it back in Menlo Park. And I think investors have worked all this out too. While Facebook currently sits 15% lower than the record highs of earlier this year, watch as the market very quickly pushes away any concerns about brand trust and buys back into the brand.

For the second quarter of 2021, the company’s revenues were up 56% to $29bn. Expect Facebook to buck all this criticism and continue to increase those figures when it reveals its third- and fourth-quarter results later this year. The one thing that you can trust about Facebook is its continued performance.

There is a difference between trust of the customers and trust of the users. What you’re showing here is trust of FB users while customers are the advertisers who are happy with the growing reach and (toxic) engagement. The users are the product FB is selling and their trust is irrelevant.

With such low user trust I think the door is wide open for a new social network that will challenge FB by offering human connection that is not vile and toxic.