Do you have a strategy worthy of a brief? These three questions will tell you

New research shows marketers are terrible at briefing agencies. To start putting that right, ask yourself whether your marketing strategy meets these criteria.

The IPA has been knocking around for over a century and, throughout that time, it has done incredibly important and useful work for advertising agencies. I did a couple of courses with them back in the 1990s and was always struck by their boutique professionalism, which contrasted so positively with so many big, dumb industry groups.

The IPA Effectiveness Awards have long been the high water mark, not just for advertising effectiveness, but for brand strategy in general. Long before Uncle Pete and Uncle Les were famous, the IPA provided a key platform for their work. Most importantly, the IPA’s booklets on all things from agency selection to remuneration were the ultimate industry guide for those of us finding their way back in the day.

So, when the team at BetterBriefs asked if I wanted to help them write a new mini guide about briefing in partnership with the IPA, I had agreed before reaching the end of the email. I grew up with these guides, and if I could be part of the next generation of them, I was Roy Keane.

The opportunity was there because of the stunning work the BetterBriefs team did last year to reveal the sorry state of client briefing in this country and others. I’d heard it over beers for decades, but the quantitative evidence they produced confirmed what so many agencies knew, and what so many clients did not: that briefs had become increasingly dogshit, thereby imperilling the all-important link from strategy to tactical execution.

The horror of marketers’ strategic bankruptcy is about to be laid bare

And when you compare the 2021 data to an earlier IPA survey conducted almost 20 years ago, it’s also apparent that the quality of briefing is in abject decline on almost every metric. It was not always this bad.

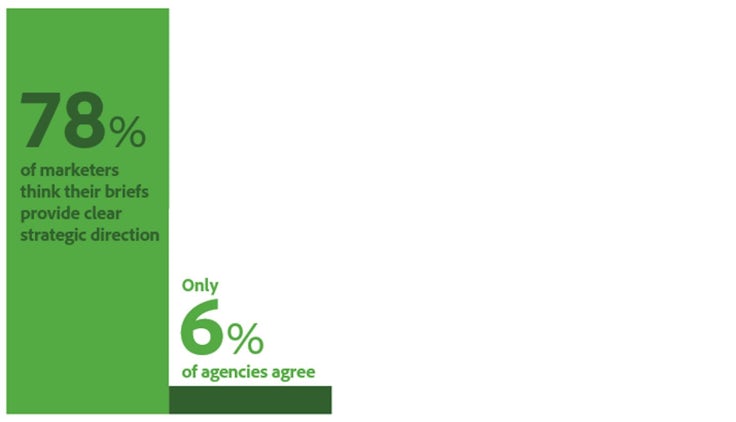

And it’s not just that bad briefs are a key issue for marketers, it’s that marketers don’t think they are a key issue. The killer chart is the one showing most marketers reporting their briefing skills as good and most agencies, on the receiving end of these briefs, thinking the exact opposite. It’s one thing to be bad in the sack. It’s quite another to be bad in the sack and think you are Casanova. Specifically, you’ll never improve or seek advice on improvement while that misplaced confidence remains.

And improvement is not such a herculean task when it comes to briefing. Of all the many challenges of marketing, I would put briefing in the top-right quadrant of the importance/improvement matrix. You have to be able to brief well to get anywhere in marketing, but exposure to a few days of training will get you in a place to be able to do it very quickly. Sure, you will get better with time. But briefing is not that difficult if you know what you should be doing. As such, its an easy win for all marketers.

That said, there is a deeper challenge implicit in all this talk of briefing. Our agency brothers and sisters remain convinced that the fault lies with our inability to brief well. I don’t disagree. But prior to this challenge of communication and relationship is a deeper more fundamental question of strategy. All the briefing expertise in the world will not help you if your core strategy is shithouse or not ready for tactical execution; or, as is often the case, simply does not exist in any proper sense of the word.

Just as diagnosis feeds your strategy, strategy predicates any brief. And it is clear that so many brands simply do not have the strategic chops to brief anything to their agency partners. They might be able to get away with it around their own addled corridors, but the brief is the strategic moment of truth where they must reveal the thinking to others. And in so many cases it is not fit for purpose.

I will leave it to the IPA and the BetterBriefs team to handle the challenge of briefing in more depth and with more expertise (you can download a copy of the new report here). For now, I want to focus on your marketing strategy and the three questions you need to answer before you even think about your brief.

Think of the rest of this column as a checklist that you should challenge your team with before you even think about advertising, or agencies, or any of the tactical tinsel that awaits. Is your strategy ready? Let’s ask three questions to discern an answer.

Targeting

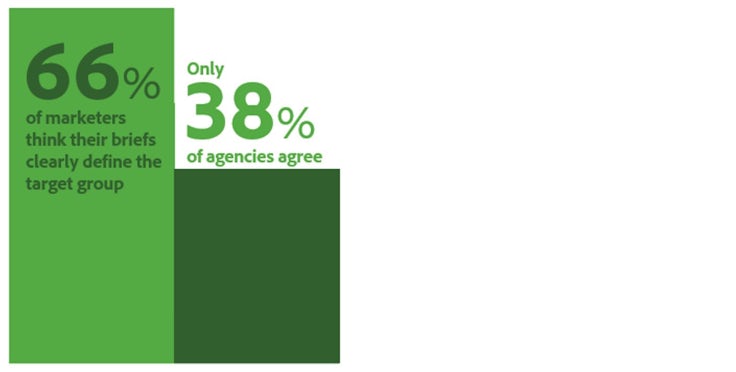

You might imagine the one thing all briefs contain is a clear sense of ‘who’. But you would be mistaken. According to the BetterBriefs data, almost two thirds of UK agencies don’t think that targeting is clearly communicated.

Hell, a third of clients don’t think their own brief contains clarity on the topic. Step back and think about that for second. More than half the briefs delivered in the UK are failing to articulate who the subsequent tactical work will be aimed at. We aren’t talking about whether the agency agrees with the targeting rationale or thinks it is possible, we are talking about a total absence of clarity on one of the most fundamental questions for creative, media and marketing impact.

To be fair, the targeting question has become infinitely more complex than it was a decade ago. Before you even get to the prosaic business of describing targets, you must first agree as a company what your philosophy of targeting is. If you are a strict Ehrenberg-Bassian, then it follows your target will be the sophisticated mass market. But even that most basic and brutal of targeting choices presents questions. Specifically, the sophisticated bit.

Knowing you are a national insurance company that subscribes to a mass-marketing approach still leaves the thorny, sophisticated question of where you draw your box. It’s clearly not around every person in the UK. It’s equally clearly not just people who have ever bought insurance. The grey area between these two possible boxes is imprecise, but it needs precision if this is the targeting rubric that you want to communicate.

Any fool can build a rhombus and populate it with stupid words. Only a proper marketer can narrow it down to a handful and communicate it clearly to the agency.

And, for many marketers, it is not as simple as mass marketing. For reasons of budget, many brands simply cannot follow the sophisticated mass marketing route, even if they philosophically fall in line with the Dark Lord of Penetration, Byron Sharp, and his red corpus. So they must either zoom in on their category to find a suitable, scale-appropriate playing field for the services – bicycle insurance, for instance – or they should segment the mass market in a meaningful way that allows them to focus and succeed, but with a scale that still produces the financial results they desire. A focus on the Northern metro cities for customer recruitment might be an example.

And there are other reasons, more strategic in nature, that might tempt marketers to augment the mass-marketing route and dive into the world of segmentation. I firmly believe companies that have the budget should aim at the sophisticated mass market to build their brand. But I am equally convinced that when it comes to the activation goals of a promotion, or piece of digital marketing, or sales force conversion, that segmentation makes sense.

In these two-speed cases, a marketer needs to be able to outline first the sophisticated mass market to which they want to aim their brand campaign, and then the more operational targets – and there will be more of these – on which their performance marketing will focus.

Finally, there are still those who subscribe to a traditional STP (segment, target, position) philosophy and have one or more target segments that they wish to go after. And no matter what the driving philosophy of targeting, make sure a customer portrait is included in the final strategy.

For too long, we have conflated those fictional, upbeat customer personas that were built from bullshit, aspiration and stock photos with the more prosaic, data-driven customer portraits that tell a true story of the market. Be clear on who you are targeting. On how many targets. And, for each, use your qual and quant data to paint a picture of who this customer is.

Why major brands are pledging to make pitching more ‘positive’

Don’t restrict your portrait to the category you operate in either. Be mindful that a proper portrait is market-oriented and tells the story of the customer, not your brand. I have worked for so many banks whose customer portraits focus exclusively on the mortgage these customers seek, not the bigger house search to which a mortgage forms only a fractional part.

Show the big picture. Who are these people? What do they currently do? What floats the customer’s boats? What deflates it? What are the ‘jobs to be done’ in their world? The alternatives they are also looking at? Put flesh on the targeting bones using the data you used to make the initial targeting choices. And, remember, a good customer portrait is usually a miserable, challenging thing. It’s not what we want the customer to do, it’s what they actually do.

Positioning

There has been a lot wrong with brand positioning for a very long time, and it shows in the quality of the briefs that agencies must work with on a weekly basis. Again, in principle, it should be a base requirement of any brief to articulate what the brand position is. Clearly, there may be some work downstream by the agency on specific messaging. But a brand should have, at its core, clarity on what it stands for and what it wants to reiterate and reinforce to its target customers.

But here, we run into one of the great scandals of modern marketing. Most marketers have forgotten that positioning was always meant to be a means to an end. The position is simply the intended brand image, if things go to plan. I always ask clients to zoom in on a customer walking down the street and to imagine they have three vacant brain cells for their brand. Ideally, what would we like each brain cell to contain? That, right there, is positioning. It’s the intention that precedes the image.

Unfortunately, most marketers have convinced themselves that positioning is an end in itself. It’s a deck with 10 slides. It’s a chart with an onion that has many layers and even more words. It’s a brand book with 40 pornographic, self-indulgent pages and no mention of the customer. It’s brand values, brand purpose, brand character, tone of voice, brand attributes, brand this, brand that.

Since the turn of the century, marketers have been too scared, too insecure, too transient to be choiceful. They have seven concepts when one is the maximum number you need to position a brand. Call positioning whatever you want but don’t overcomplicate it with multiple models. When you do that you end up with 20 different words to position the brand, when three or four was always the limit for true effectiveness.

Any fool can build a rhombus and populate it with stupid words. Only a proper marketer can narrow it down to a handful and communicate it clearly to the agency. More is not more in the game of positioning. It’s less.

The lessons of differentiation are clear. You will never find anything unique. You will never own an attribute. But if you are choiceful, and you double and triple down on the associations that matter, and you do that for an uncomfortably long time, you can build brand. The target consumer will only be clear if you are clear on what your brand stands for. And if you can communicate it to an agency in a brief.

Objectives

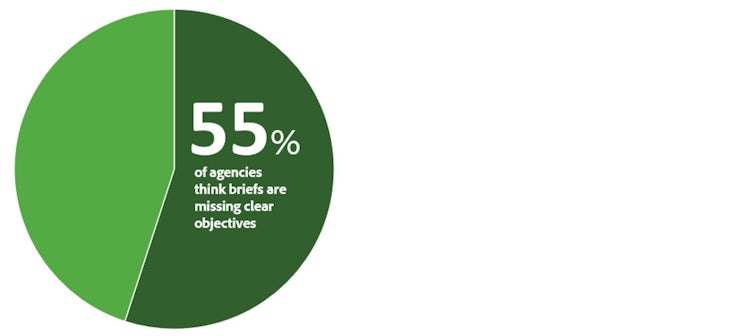

At the epicentre of good briefing, and all that is currently wrong with brand strategy, are objectives. Even if a marketer is clear on who they want to target and what their brand position consists of, the strategy is still not complete without clarity around what the brand wants to do that target.

Is this about salience? Is it better consideration? Is it price insensitivity? About changing our perception as an unhealthy brand? Is it about buying more? Or more frequently?

There are a myriad of levers a marketer could potentially pull to drive sales, market share and profitability. It’s not the agency’s job to work back from a dumb goal like ‘increase sales’, it’s the client’s. And the current marketing world is just not staffed with enough marketers good enough to work out the best objectives and communicate them accordingly.

Your first job as a marketer is to review all the possible levers you might want to pull in the year ahead. Look at brand perceptions. Look at your funnel. Look at the corporate strategy. Look at your market research. And then wave your marketing magic wand and lay out the things you would like to achieve.

And then kill. Because the research on objective-setting suggests, once again, that less is more. The long-standing research on setting and achieving corporate strategic objectives suggests a ‘handful’ of objectives is the optimum number.

I’ve long believed that a single marketing objective is the best way to have the most impact, and I have senior friends at Google who agree. This singularity of focus and the ‘handful rule’ are not incommensurate with one another. If you adopt a two-speed targeting approach, or have multiple target segments, there are likely to be several targets in your plan and each should, ideally, have a single objective associated with it. Add these objectives up and – hey presto – your plan should hinge on four or five clear objectives.

There is a tricky question often asked of marketers: how do you assess the success of your campaign? It’s a trick question, because there is only one answer and it has nothing to do with post-campaign assessment.

Simply answering the three questions above with clarity and focus will put you in the top 10% of marketers. The bar is really that low.

The only way to measure success is to return to the original objectives that sparked the initial tactical work and remeasure them at a later date. That means writing objectives based on a measured number from customer data, which serves to underline the issue that needs to be fixed and which provides a benchmark that needs to be compared to when the work is done.

That also demands a date of completion for the objective to be achieved and remeasured. And by the time you add the target segment and the focus for the objective, you should have a single sentence that passes the ancient test of SMART objective setting.

Ignore all those idiots that have a specious issue with SMART objectives; they are nit picking, and the shithouse level of marketing planning at the moment demands a basic solution. A specific objective, measured pre and post, that is ambitious enough to make the money but realistic enough to be achieved by a certain time, is the way to express your objective.

Asking a marketer for their objectives behind a tactic is a sliding-doors moment. You either get a lot of guff and a six-minute soliloquy of stupidity and vagueness, or a smile and a single slide saying: “Increase consideration for Acme among the Heavy Lifter segment from 20% to 45% by EOY.”

Guess who will brief better. Who will get better tactics. Who will more likely achieve their goals. And who will learn from the process and become better as a result.

Many marketers stumble with the 45% bit. They know their benchmark, but what can they achieve? Good agencies can feedback here using their experience from other clients. And it gets easier with experience. Most young marketers overstate their objectives and gradually learn that a double-digit increase in brand preference is not just challenging, it’s practically impossible in most situations.

The further down the funnel you focus, the tighter and harder every yard of growth becomes. One wonderful asset comes from the fantastic research firm Tracksuit, which recently published a report on what its clients have managed to achieve on the various ladders of the funnel. It’s useful context and will help in the challenge of setting suitably smart objectives.

The message from BetterBriefs and the IPA is clear. Most marketers are failing not only their agencies but also their own brands by being shit at briefing. And yet briefing is not that hard to master.

First, take time to build a proper marketing strategy with clarity on targeting, positioning and objectives. Remember, you don’t have to have a perfect answer to these questions. No such thing exists. Just an answer. Simply answering the three questions above with clarity and focus will put you in the top 10% of marketers. The bar is really that low.

In about another 20 years, the IPA will write another report on briefing. I see no reason why we cannot, as an industry, improve and return better numbers than the current woeful status quo provides. The stakes are high. The bar is low. And the challenge of briefing better really ain’t that hard.

You can download a copy of the new IPA Guide on briefing here.

Mark Ritson is (annoyingly) once again the PPA Columnist of the year. He teaches much more on the topics of targeting, positioning and objectives in his Mini MBA in Marketing courses.