It may be tainted, but don’t underestimate the power of brand love

Although the concept of ‘brand love’ was overused and went out of fashion, it remains an insightful way to consider consumers’ attitudes towards brands.

“You do realise that this is fantastically untrendy research?” I explained to the team from Savanta, when they approached me to give the launch speech for their 2022 Most Loved Brand Award. “To top things off,” I added, “you’ve only gone and split out your findings by segments of the market too. Which is also fantastically uncool.”

It’s true, is it not? The merest mention of ‘brand love’ elicits a collective groan from the gaggle of opinion leaders that monitor every discussion about marketing. And slicing anything these days by segment opens up the obligatory critique about the pointlessness of segmentation and the reinstalled dominance of mass marketing.

And yet here was a market research company with a massive sample, a scalar question about brand love and lots of league tables going in all kinds of interesting directions. I took the gig, of course. Partly for the money but also because Savanta’s proposal made me think about why we all collectively fell out of love with brand love, despite so passionately embracing it not that long before.

Cast your mind back to the crazy days of the late 20th century and brand love was everywhere. Academics talked about brand relationships in a manner akin to marriage. Every third case study of branding success ended with consumers getting a tattoo of the company’s logo on their upper shoulder. And best-selling authors climbed over each other to come up with ever more ejaculatory metaphors for brand loyalty, obsession, love, passion, delight or intimacy.

In a climactic moment, Saatchi & Saatchi CEO Kevin Roberts published the book Lovemarks in 2004. It was a future “beyond brands”, predicated on the love between enraptured consumers and eager, consenting brands. One in which “mystery, magic and sensuality” all played their part. Dim the lights…

Goodbye to love

And then things changed. The fire went out. The leopard skin rug was pulled from under the intertwined bodies of brand and consumer. The Barry White music stopped. And the lights came on. All passion halted.

In 2007, Havas published the results of global research indicating most people would not care if 74% of brands disappeared. It’s one of those factoids that escaped the mundane cage of its broader, more boring report and pricked the consciousness of marketers everywhere. You’ve heard the Havas stat before. It’s been played back to you in presentations and articles so many times you – like most of us – have committed it to factual memory alongside the belief that people don’t actually care about brands.

And yet when you step back and interrogate the fact itself, it is slightly nonsensical. People would not care if 74% of brands disappeared. Which people? What, all of them? Which 74% of brands? And is this really that surprising? I don’t give a crap about most of the brands out there. Especially the ones that have fuck-all relevance for my life – diet drinks, nappies, tampons etc.

More importantly, what marketers did when we saw that number 74 was focus upon it. And what we did not do, even for a second, was think about the 26. Most consumers would not care if three quarters of brands disappeared overnight. Wow! But they would care about the remaining quarter. That does not equate directly to love, but it suggests that our industry took the 74% and ran a little too far with its implications.

There has to be room in any theory of brand management for affection, love and even loyalty.

Linked to the Havas factoid was the emergence of the Ehrenberg Bass Institute and a new school of brand thinking. Brands grew through mental and physical availability, not love. Salience was the new engine for success. Brands were little, cognitive things that needed to come to mind in buying situations. There was no room in this clean, efficient, cerebral paradigm for something as soft and emotional as love. Pull yourself together.

And, as usual, there is much to be lauded in the impact of Ehrenberg Bass on marketing thinking. Marketers had lost the branding plot in the late 1990s and were overstating the import and impact that brand had in consumer’s lives. They had transposed their own undivided, 50-hour-a-week devotion to their brand onto a much more distracted, unmotivated consumer, who barely thought about the brand once a year, never mind once a day.

But, also as usual, there was a distinct sense that the much-needed rebalancing of brand theory went just a little bit too far in the opposite direction as a result of the Ehrenberg Bass intervention. The branding pendulum needed to swing away from the flaming red bullshit of brand love, but it passed too far the other way into the monochrome rationality of category entry points. Perhaps there was something to value in affect and brand love, just not as much as we had all once thought.

Where is the love?

If nothing else, marketers should always avoid a focus on either head or heart at the expense of the other because, if we have learned anything over the last century of persuasion research, it is that the two are as intertwined conceptually as they are biologically. Even those of us who now accept the importance of salience at the very centre of brand operation would do well to remember the intense impact that emotion has in generating salience in most people, most of the time. If I ask you to close your eyes and think of a person – go on, go on – the chances are the person that sprang into your mind was also one of those you feel the strongest about. Perhaps even the one you love.

There has to be room in any theory of brand management for affection, love and even loyalty. All three were certainly overplayed and overstated in decades past. But committing the equivalent sin of underestimation today does not absolve the exaggerations of the past.

We should give a little bit of our time to brand love, especially when it is measured the way Savanta do it, which is as a gestalt. Other surveys create very specious breakdowns of the component parts of brand love and then accumulate them into a dreadfully ridiculous scoring system. I like a good old-fashioned gestalt measure, in which the consumer gets to define what they mean by ‘love’ and then assess it with a simple six-point scale, with love at one end, indifference in the middle and dislike at the other end.

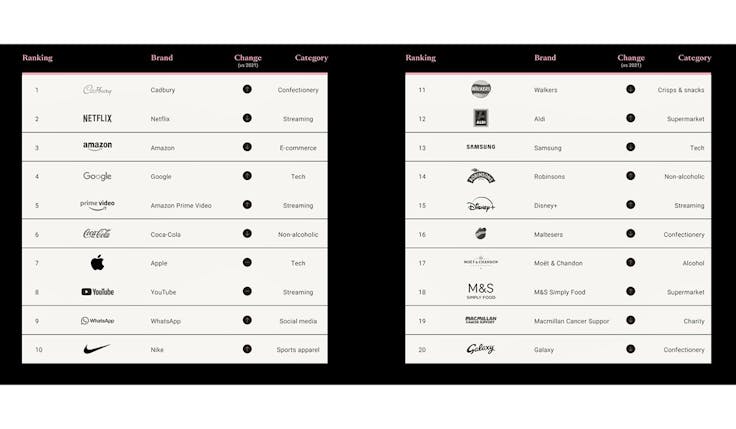

When you ask this question of 200,000 British people, you learn some interesting things. You learn that Cadbury is now the most loved brand in the country. Sure, consumers are better disposed towards loving brands in some categories than others, and these therefore enjoy an unfair affection advantage. Selling chocolate, as opposed to anti-perspirants or insect repellent, provides an enormous boost to your potential lovability.

But that category advantage is an inherent factor in brand love and should not be dismissed or balanced out. In Cadbury’s case, the brand also has history on its side. Thanks to its founder John Cadbury, the brand’s DNA was forged in the furnace of Quakerism and the love for every fellow man and woman. If your aim is brand love, it helps to work on a brand that was set up as a literal act of love. But the current Cadbury team, or rather those at Mondelez, deserve credit for passing the eternal challenge of Not Fucking It All Up.

The top 10 is also revealing. As an army of bedroom-bound teenagers can confirm from under the duvet, we live in an era of digital love. More than half of the most loved brands are entirely digital in nature. And with digital comes the associated realisation that relatively youthful brands can sometimes demand the broadest levels of affection. Half the top 10 list did not exist before the 1990s. In contrast, the presence of Coke, Cadbury and Nike also reminds us that age is no restriction either.

All out of love

And it is as much about the brands that don’t feature in the love list as the ones that do. Facebook is notable in its absence from the top 10 this year. It’s even more notable because the brand does not even feature in the top 100. WhatsApp has proven a valuable replacement in the top 10, but I bet Meta cannot wait for the metaverse to arrive and all the opportunities for synthetic, artificial love that it will surely confer.

The best insights come from the slicing and dicing of the data across the ancient boundaries of geographic and demographic separation. Once again, we must thank Ehrenberg Bass for resurrecting mass marketing from its untimely grave. And, once again, we must acknowledge that we may have gone a little too far in rejecting any and all slicing of the market.

Most segmentation is pants, I agree. But not because segmentation is pointless in general, but rather the specific attempt at segmentation created by a marketing manager is not fit for purpose. When it comes to STP (segment, target, position) don’t hate the game, hate the player.

The joy of such a stupendous sample for the brand love research is that you can slice it without fear of diminishing the confidence levels or intervals of the data. And when you do the slicing, there are some interesting insights to be had. The difference between stereotypes and segments is data – we should remember that when we try and pigeonhole millennials as one thing and gen X as another. But we also need to remember that distinction when the data throws up politically uncomfortable insights that would usually prove unacceptable for public airing.

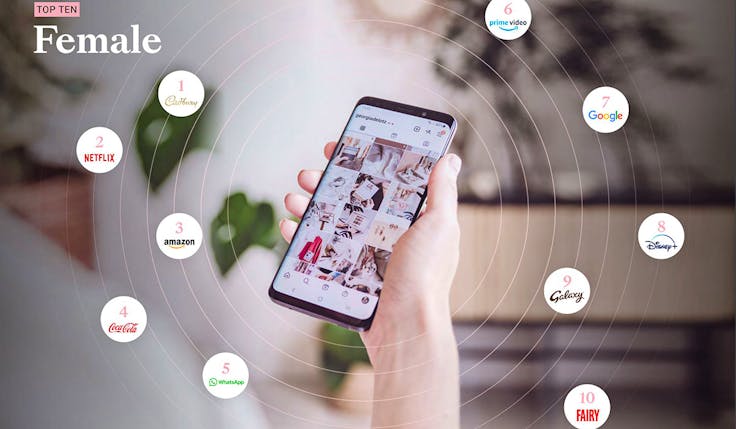

If I got up in front of an audience and told them that women love Fairy dish detergent, I’d be lucky to escape the stage with my genitals still connected to my body. And rightly so. But the data doesn’t lie, and there sits Fairy as one of the most loved brands in Britain, for women. And it makes absolutely no dent on the male list. Instead, their brand love is reserved for their Playstations. What a fantastically depressing insight into modern gender roles.

If I went up north and contrasted mineral water-drinking Londoners with the sugar-loving fatties of Scotland and Northern Ireland, my testicles (and probably everything connected to them) would be again under threat. And yet, the top 10 of Celtic brand love features Maltesers, Fanta and Iron Bru as well as Cadbury, while the London sample doesn’t love a single confectionery brand, preferring Evian instead.

There are differences to be found in the segments of the market. Just as there still is some value in thinking about brand love – about how it forms and the benefits it then bestows. Now, if you’ll excuse me, as a card carrying member of the Northern British demographic, I am off to enjoy my glass of Robinsons Barley Water, a Galaxy bar, a Creme Egg and a 10-hour binge session on Netflix. Enjoy your Evian and jogging in your Nike trainers, you Southern wankers.

Mark Ritson is PPA Columnist of the Year (again) for 2022. He teaches many of the concepts discussed in this article on the Marketing Week Mini MBA courses in Marketing and Brand Management, both of which start again in September.

Comments